Lesson Three: Votes for Women, A Voice for All: Helen Keller, Suffragist

Before Teaching

Main Idea

Helen Keller never ceased to demand that women, the poor, and the disenfranchised be afforded an equal chance to live a full life. The digital Helen Keller Archive holds a rich collection of her writings agitating for women’s suffrage. These letters, articles, and speeches reveal the breadth and depth of Helen Keller’s advocacy for women’s voting rights, including the intersection of her beliefs about suffrage and economic justice.

Overview

Students find, read, and analyze primary source documents in the digital Helen Keller Archive related to women’s suffrage. Through close reading and guided exploration, students learn about Helen Keller’s activism in support of suffrage and analyze her multi-pronged and audience-specific arguments.

Teachers may expand this lesson with written or oral performance tasks. Guidance for implementing a Document-Based Question discussion and essay are included in the second half of the lesson plan.

Note: This lesson focuses on Helen Keller and her support for women’s right to vote. It works best in conjunction with broader study of the 20th century suffrage movement and the passage of the 19th Amendment. If you are in need of more comprehensive suffrage lesson plans, see the Resources section of this document.

Learning Objectives

- Read and understand primary source documents from the early 20th century.

- Analyze and dissect arguments in favor of women’s suffrage.

- Identify specific evidence used to support a primary argument.

- Digest and summarize complex documents to present to classmates.

Guiding Questions

- How do I use primary sources in a digital archive to understand history?

- Who is Helen Keller?

- What was Helen Keller’s role in the women’s suffrage movement?

- What methods did Helen Keller use to campaign on behalf of women’s political empowerment?

- What other political, social, and economic issues did Helen Keller link to the right to vote?

Materials

- Computer, laptop, or tablet

- Internet connection

- Projector or Smartboard (if available)

- Worksheets (provided, print for students)

- Pen/Pencil/Paper

Time

Core Lesson: 45-60 minutes

“Making A Difference” Activity: 30 mins

Document-Based Question Discussion and Performance Task: 60-90 minutes

About the Helen Keller Archive

Historical Background

The Helen Keller Archive at the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) is the world’s largest repository of materials about and by Helen Keller. Materials include correspondence, speeches, press clippings, scrapbooks, photographs, photograph albums, architectural drawings, audio recordings, audio-visual materials and artifacts.

The collection contains detailed biographical information about Helen Keller (1880-1968), as well as a fascinating record of over 80 years of social and political change worldwide. Keller was a feminist, a suffragist, a social activist, and a pacifist, as well as a prolific writer and published author. The AFB began collecting material by and about Keller in 1932, and the collection has only grown since then. Most importantly, the Helen Keller Archive is being made accessible to blind, deaf, deaf-blind, sighted and hearing audiences alike.

Important Definitions

Suffrage: The right to vote in political elections.

Women’s Suffrage: The right of women to vote in political elections.

Suffragist: An advocate for the right of women to vote.

Franchise: The right to vote; the rights of citizenship.

Enfranchise: To give a right or privilege, especially the right to vote.

Disenfranchise: To deprive, restrict, or limit a right, especially the right to vote.

Evidence: Factual information used to support a claim. Evidence can take many forms, including statistics/empirical data, anecdotes, documents, testimony (expert or eyewitness).

Rhetorical devices: Writing techniques used to convey an idea or persuade an audience. For example: Allusion, analogy, metaphor, pathos, parallelism.

What is the difference between suffragist and suffragette?

In the early 20th century, both terms were used by English-speaking people advocating for women’s suffrage. In the United Kingdom, suffragette was the term preferred by the more radical members of the movement. However, in the United States, the term suffragette was considered demeaning, so this lesson uses their preferred term, suffragist.

Accessibility

By “accessibility,” we mean the design and development of a website that allows everyone, including people with disabilities, to independently use and interact with it. For more detail, read and review the digital Helen Keller Archive Accessibility Statement. (https://www.afb.org/archiveaccessibility)

Glossary

These are names and events which appear in the primary source worksheets. If students ask follow up questions about these unfamiliar names, here is a brief summary of each with relevant details. However, students should be able to draw all inferences essential to a basic understanding of the documents from the documents themselves.

Mrs. Grindon: Rosa Leo Grindon, a British suffragist and Shakespeare scholar. At the time she was corresponding with Helen Keller, she was living in Manchester, UK.

Mr. Zangwill: Israel Zangwill, a British writer and Zionist activist. Mr. Zangwill spoke in favor of women’s suffrage, particularly of the more militant tactics used by radical members of the suffrage movement.

Miss Pankhurst: Emmeline Pankhurst, a leading British suffragist. Beginning in 1908, Pankhurst was arrested multiple times for her activism and used hunger strikes to protest her imprisonment.

Suffrage March in Washington: Alice Paul and the National American Woman Suffrage Association organized a march on Washington D.C. the day before President Wilson’s inauguration in 1913. While the march attracted thousands of women, spectators (primarily male) also gathered to jeer at, trip, and grab the marchers, and the police did little to end the harassment. One hundred marchers were taken to the local hospital. Helen Keller was scheduled to speak at the event, but was so unnerved by the experience that she was unable to deliver her speech.

David I. Walsh: The first Irish-Catholic Democratic Governor of Massachusetts (at the time, a Republican-leaning state) and an active supporter of the fight for women’s suffrage in his state. At a 1915 suffrage march in Massachusetts, Helen Keller presented Walsh with a letter thanking him for his work.

The Woman’s Party: The National Woman’s Party, a political party active in states where women had the right to vote. In 1916, the party’s primary goal was a federal amendment securing women’s right to vote.

Part 1: Core Lesson Plan

1.1 Ask and Discuss:

- Who is Helen Keller? What do you know about her life?

- Did you know that Helen Keller was a suffragist?

1.2 Explain:

- Helen Keller lost her sight and hearing at a young age but learned to tactile fingerspell, read, write, speak, and graduated college.

- Like other women of her era, when Helen Keller came of age, she was denied the right to vote because of her gender.

- Women’s suffrage was one of many causes that Helen Keller fought for during her lifetime.

- Helen Keller followed the news about suffrage, corresponded with suffragists, and wrote and spoke out on behalf of the women’s suffrage movement.

1.3 Optional:

For classrooms that have not already studied the women’s suffrage movement, the following is a brief introduction to the suffrage movement. (Skip to 1.4 if not using.) We have provided optional images (included in the “Resource” section of this document) and slides.

Explain:

- Until the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, women did not have the right to vote nationwide.

- However, as early as 1890, some women could vote on a state level.

- In our state, women could vote beginning in [Year].

- Ask: What other groups of Americans have been denied the right to vote? Why were they denied the right to vote?

- American women were demanding the right to vote even before the United States won its independence.

- Women began to work together to demand the right to vote in the 1840s.

- The 1848 Seneca Falls Convention brought together hundreds of women looking for change.

- The movement lost momentum during the Civil War, but re-emerged in the late 19th century.

- Ask: Why is the right to vote so important? What is the role of voting in a democracy?

- Today, we are going to analyze primary source documents on women’s suffrage. Specifically, we are going to look at speeches, articles, and letters by Helen Keller.

1.4 Ask and Discuss:

- Have you ever heard of an archive? Where/in what context?

- What is an archive?

- Have you ever used an archive? What about a digital archive?

1.5 Define an Archive:

- An archive is a collection of unique documents, objects, and other artifacts that has been organized to make sense of a collection so that people can find what they are looking for.

- Most archives are physical. For example, they have an actual space full of actual documents organized into boxes and folders.

- Some archives are also digital. For example, archivists have scanned and labeled the artifacts in their collection and made them available via the internet.

- Today, we are going to use the digital Helen Keller Archive. This archive is the world’s largest collection of artifacts by and about Helen Keller. It is also fully accessible for people with disabilities. That means that people with disabilities, including those who have low vision or hearing, can use this website independently.

Part 2: Core Lesson Activities

2.1 Do:

- There are six documents to work on in class:

- Letter from Helen Keller to Mrs. Grindon about women’s suffrage written January 12, 1911

- Speech written by Helen Keller regarding women’s suffrage and the freedom of men and women, March 3, 1913

- Letter from Helen Keller to David Walsh, Governor of Massachusetts, advocating for women’s suffrage, 1912

- Article by Helen Keller “Why Men Need Woman Suffrage” republished in Outlook, originally published in October 17, 1915 edition of the New York Call

- Helen Keller’s speech to delegates of the new Woman’s Party in Chicago endorsing suffrage movement, June 11, 1916

- Speech given by Helen Keller in favor of women’s suffrage entitled “Why Woman Wants to Vote.” 1920

- Break students up into groups and assign one document to each group.

- Distribute the corresponding document worksheet to each group.

- Worksheet: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1911 Letter to Mrs. Grindon (HTML)

(Downloadable PDF: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1911 Letter to Mrs. Grindon) - Worksheet: Helen Keller’s Undelivered Speech on Women’s Suffrage, 1913 (HTML)

(Downloadable PDF: Helen Keller’s Undelivered Speech on Women’s Suffrage, 1913) - Worksheet: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1912 Letter to Governor Walsh (HTML)

(Downloadable PDF: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1912 Letter to Governor Walsh) - Worksheet: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1915 Article “Why Men Need Woman Suffrage” (HTML)

(Downloadable PDF: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1915 Article “Why Men Need Woman Suffrage”) - Worksheet: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1916 Speech to the Woman’s Party in Chicago (HTML)

(Downloadable PDF: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1916 Speech to the Woman’s Party in Chicago) - Worksheet: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1920 Speech “Why Woman Wants to Vote” (HTML)

(Downloadable PDF: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1920 Speech “Why Woman Wants to Vote”)

- Worksheet: Analyzing Helen Keller’s 1911 Letter to Mrs. Grindon (HTML)

- Review the questions with the class. While all documents and questions are slightly different, the questions all fall into the same broad categories: Sourcing, Close Reading, Contextualization, and Rhetoric and Analysis.

2.2 Explain:

- The document may mention people and events that you aren’t familiar with. That’s OK! If you are curious, you can ask me after you finish your analysis.

- Analyze these documents with your group and answer the questions. When you are finished, your group will summarize your document for the class.

- Navigate to the source on your group’s source worksheet.

- Optional: For an additional challenge, you can remove the links from the worksheets and ask students to search or browse to the document described in their worksheet.

2.3 Demonstrate:

When students have located their document, show them where to find:

- Transcription of the selected image. You may read your source directly from the image of the source or using the transcription.

- Contents of this item (multiple document images/pages). Many of these sources have multiple pages. Use the “Next Image” button or “Contents of this Item” box to navigate to the next page.

- Metadata. The metadata contains essential information about your source, like when it was written and who wrote it.

2.4 Optional:

For classes or students who need practice constructing and deconstructing arguments, you can model the process using an excerpt from “Why Woman Wants to Vote”, a 1920 speech by Helen Keller. (Skip to 2.5 if not using.)

“We demand the vote for women because it is in accordance with the principles of a true democracy. Many labor under the delusion that we live in a democracy. I have to smile– several ways– when I read that ours is “a government of the people, by the people, and for the people.” We are neither a democracy nor a true representative republic. We are a government of parties and partisans, and lo, at least half the adult population may not even belong to these parties.”

Helen Keller is arguing that women should be able to vote because it is in accordance with democratic principles.

She supports her argument by invoking shared values (“principles of true democracy” “a government of the people, by the people, for the people”), undermining widely held assumptions (“many labor under the delusion”) and citing statistics (“half the adult population may not even belong to those parties”).

The Big Idea

Helen Keller assumes that we all believe in democracy and value living in a government by, of, and for the people. She points to the simple fact that half of the people in that democracy cannot vote, and therefore cannot participate in the government. She contends that America is not a democracy because women cannot vote. If the nation were to accept her argument and extend the vote to women, she implies, we would then live in accordance with true democratic principles.

2.5 Presentations:

While each group presents, take notes (or ask a student to take notes) on the board or slide.

2.6 Closing Conversation:

- What is similar/consistent about Helen Keller’s arguments in these documents?

- What is different? How do her arguments change from document to document? Why do you think they change?

- If necessary, highlight differences in the audience Keller addresses. For example, compare the following:

- What do these documents tell us about Helen Keller? About the women’s suffrage movement?

- How do you think Helen Keller’s identity and social status—for example, her gender, race, and class—shaped her perspective on women’s suffrage?

Part 3: Extension Activity: “Making a Difference”

- Review assignment instructions.

- Distribute “Making a Difference” worksheets (PDF format).

Part 4: Extension Activity: Document-Based Question (DBQ)

- Preview the extension activity

- Distribute the documents, including the graphic organizer (Word file) or graphic organizer (PDF).

- Introduce each document individually.

- Read each excerpt together as a class.

- Share contextual information.

- Discuss the main idea of each document.

- Review assignment instructions.

Resources

Websites:

Helen Keller Archive

(www.afb.org/HelenKellerArchive)

American Foundation for the Blind

(www.afb.org)

Women’s Suffrage Educational Resources:

Teaching Tolerance

www.tolerance.org/classroom-resources/tolerance-lessons/womens-suffrage

5 Black Suffragists Who Fought for the 19th Amendment—And Much More

(History.com/news/black-suffragists-19th-amendment)

National Education Association

www.nea.org/tools/lessons/63472.htm

Library of Congress

www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/lessons/women-rights/index.html

National Women’s History Museum

www.womenshistory.org/resources/lesson-plan/road-suffrage

Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument (timeline)

www.nps.gov/articles/us-suffrage-timeline-1648-to-2016.htm

Images:

Figure 1. Helen Keller visiting Menlo Park Observatory, 1930

American Foundation for the Blind, Helen Keller Archive

Link: https://www.afb.org/HelenKellerArchive?a=d&d=A-HK07-01-B021-F07-001&e=——-en-20–1–txt——–3-7-6-5-3————–0-1

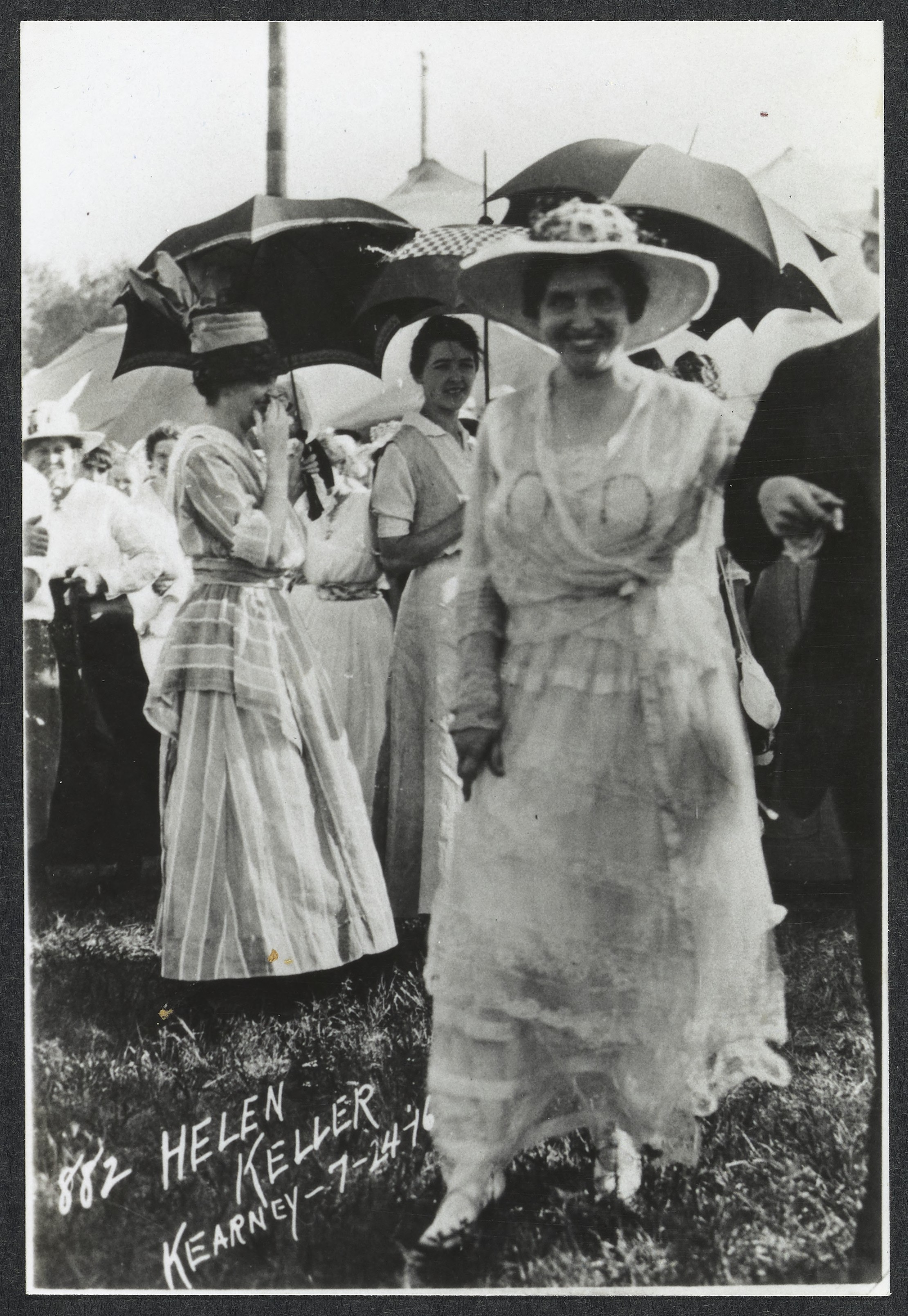

Figure 2. Helen Keller outdoors with a group of women, 1916

American Foundation for the Blind, Helen Keller Archive

Link: https://www.afb.org/HelenKellerArchive?a=d&d=A-HK07-01-B020-F09-005.1.1&e=——-en-20–1–txt——–3-7-6-5-3————–0-1

Figure 3. Alison Turnbull Hopkins at the White House protesting, 1917

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Link: https://www.loc.gov/resource/mnwp.160032/

Figure 4. Screenshot of the digital Helen Keller Archive

The digital Helen Keller website address is https://www.afb.org/HelenKellerArchive.

Figure 5. Newspaper clippings from Anne Sullivan Macy’s scrapbook

American Foundation for the Blind, Helen Keller Archive

Link: https://www.afb.org/HelenKellerArchive?a=d&d=A-HK05-B290-BK01-001.1.5&srpos=5&e=——-en-20–1–txt–suffrage——3-7-6-5-3-5%3a+Scrapbooks————-0-1

Figure 6. Broadside created by the National American Woman Suffrage Association

Courtesy of Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Link: https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-now/spotlight-primary-source/womens-suffrage-poster-1915

Figure 7. Screenshot of article in The Crisis, September 1912

Via GoogleBooks

Link: https://books.google.com/books?id=D1oEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA209&pg=PA242#v=onepage&q&f=false

Figure 8. Screenshot of article in The Journal and Tribune in Knoxville, Tennessee, 1914

Via Newspapers.com

Link: https://www.newspapers.com/image/584878271/?image=584878271&words=&terms=Southern+States+Woman+Suffrage+Conference

Curriculum Standards

This Lesson Meets Common Core Curriculum Standards:

Middle School

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2

Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.6

Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts).

High School

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.1

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.2

Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.5

Analyze how a text uses structure to emphasize key points or advance an explanation or analysis.

C3/National Council for Social Studies

BY THE END OF GRADE 8

D2.Civ.1.6-8.

Distinguish the powers and responsibilities of citizens, political parties, interest groups, and the media in a variety of governmental and nongovernmental contexts.

D2.Civ.2.6-8.

Explain specific roles played by citizens (such as voters, jurors, taxpayers, members of the armed forces, petitioners, protesters, and office-holders).

D2.Civ.12.6-8.

Assess specific rules and laws (both actual and proposed) as means of addressing public problems.

D2.His.3.6-8.

Use questions generated about individuals and groups to analyze why they, and the developments they shaped, are seen as historically significant.

D2.His.12.6-8.

Use questions generated about multiple historical sources to identify further areas of inquiry and additional sources.

D2.His.13.6-8.

Evaluate the relevancy and utility of a historical source based on information such as maker, date, place of origin, intended audience, and purpose.

D2.His.16.6-8.

Organize applicable evidence into a coherent argument about the past.

D3.2.6-8.

Evaluate the credibility of a source by determining its relevance and intended use.

BY THE END OF GRADE 12

D2.Civ.12.9-12.

Analyze how people use and challenge local, state, national, and international laws to address a variety of public issues.

D2.Civ.14.9-12.

Analyze historical, contemporary, and emerging means of changing societies, promoting the common good, and protecting rights.

D2.His.3.9-12.

Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

D2.His.4.9-12.

Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

D2.His.11.9-12.

Critique the usefulness of historical sources for a specific historical inquiry based on their maker, date, place of origin, intended audience, and purpose.