An Update on the Finger Reader, an On-the-Go Reading Device in Development at MIT

In March 2015, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) announced that researchers in its Media Lab had developed a prototype of a reading device that is worn on the finger. Many people in the accessibility community were very excited by this prospect. Unlike other common OCR (optical character recognition) apps that first scan and then process the page, the MIT device, dubbed the Finger Reader, reads text in real time.

The concept for the device was developed by Roy Shilkrot, an MIT graduate student in Media Arts and Sciences. He and Media Lab postdoc Jochen Huber are lead authors on a paper describing the FingerReader. Additional co-authors were Pattie Maes, the Alexander W. Dreyfoos Professor in Media Arts and Sciences at MIT; Suranga Nanayakkara, an assistant professor of engineering product development at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, who was a postdoc and later a visiting professor in Maes' lab; and Meng Ee Wong of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. Dr. Huber presented the paper in April at the Association for Computing Machinery Computer-Human Interface conference.

Shilkrot graciously agreed to be interviewed for this article. He explained, "I came up with the idea about two years ago. I thought it would be very interesting to think about reading because I know accessing print material is not a solved problem for people with a visual impairment. Because of the tactile sensitivity of the finger and the directionality of the finger when you point at something, it just made sense to think about reading and using the finger."

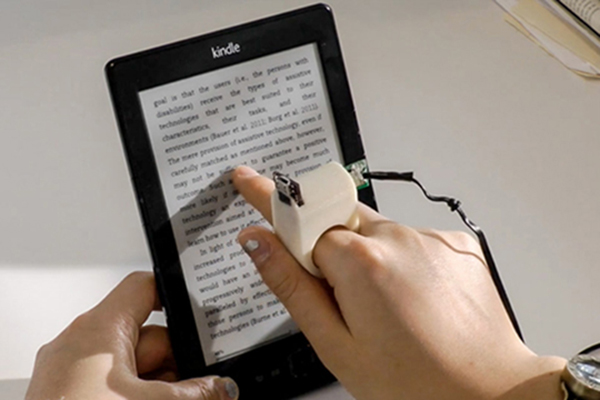

Caption: The Finger Reader (Photo curtesy of MIT.)

OCR programs such as Abbyy TextGrabber & Translator and Prizmo, Finger Reader does not need to scan an entire page before it processes text. The Finger Reader lets the user move around the page at will, voicing text detected wherever the user points the device. This is especially useful when looking for specific information or reading a menu. Shilkrot said, "We want to create a reading experience that will be closer to that experienced by a person without a visual impairment."

A new paper about the Finger Reader will be published within the next few months. Shilkrot said, "We'll go further into why we think this product is as good as or better than current solutions. What it does is sort of level the field, in terms of reading, for people with and without a visual impairment."

Physical Description of the Finger Reader

Shilkrot describes the FingerReader as "rather small, sort of like an oversized ring." He said that the ring was about the height of one average finger width and about half the distance from knuckle to knuckle. He added that the FingerReader itself, without a cable, has not been weighed, but he estimates it at about 50 grams (1.8 ounces) or less. The latest version is more like an easily adjustable rubber strap than a hard ring.

How the Finger Reader Works

The device's camera points down from where it is worn on the finger, but does not touch the page. As the tip of the finger moves along the page, the camera gets a wide view of the print. Tones play if the user's finger deviates from the current line.

Shilkrot and the research team developed a complex algorithm to convert what the camera sees into speech. According to Shilkrot, it usually takes less than half a second to speak a word once it is detected.

As the wearer's finger moves across the page, the camera uses the algorithm to process what it is seeing. Shilkrot said, "The idea of what we're trying to do is that you can always trust the device to say the word that is in front of your fingertip. The camera sits on the finger, but does not touch the page. That's how it gets such a wide view of what's there. It tracks the fingertip and it tracks the words on the page. It gives you audio cues to feel where the print is and it tries to infer the next word to say."

The FingerReader currently connects to an Android device such as a phone or tablet. The developers are working on a wireless version. Shilkrot explained, "The development process on Android is easier because it's more open. With iOS we still haven't figured out if we can connect the device and have the phone work with it. It has to do with some drivers and we don't have a definitive answer to that yet."

Testing the Finger Reader

Shilkrot expressed his gratitude to members of the VIBUG (Visually Impaired & Blind Users Group) who meet at MIT. This group was involved with recruiting test subjects for the Finger Reader prototype. Shilkrot said that most, if not all, testers were members of the group, adding, "In the name of the team I would like to thank them."

When the Finger Reader was first tested, researchers used both vibrations and audio signals, separately and together, to help guide the user's finger. There were two motors on the device, one on the top and one on the bottom. They tried three different methods: vibrations alone, tones alone, and the two together. The researchers chose to use the audio method alone since audio sensors are lighter and smaller than vibrating motors.

Shilkrot discussed further development of the Finger Reader. "There's a lot more to do on the software side and on the device side to correct things. We don't need to bother the user with these things. The user needs to be reading naturally and the device will be doing the heavy lifting."

Availability of the Finger Reader

The Finger Reader is still in the developmental stage. Shilkrot explains the timeline thusly: "We are not a company with a lot of funding; we can't hire a bunch of engineers. We're doing this in an academic route, [which] means that we have limited funding, limited people, and limited time to work on this. That's why it will take longer than people might expect, but it's definitely taking steps to where it's becoming more like a product."

Shilkrot didn't know how much the Finger Reader will cost since a final version has not yet been developed. He did mention that a user who already has an Android device will only need to purchase the Finger Reader to have on-the-go reading capability.

The Future of the Finger Reader

According to Shilkrot, many people are skeptical about the Finger Reader. He said, "We've got to keep in mind that we're researching something that has never been done before. We're trying to come up with this new way of reading and we're still trying to figure out the best way to do it. If we keep working on it, involving people with a visual impairment into our design process and our developmental process, I think we can end up with something that is good and useful." He understands that people want to feel and try the Finger Reader, but at present, more development and testing need to be done.

More articles from this author:

The Giraffe Reader Scanner Stand and the Prizmo Scanning App for iOS

The Fitbit Flex Offers Access for Blind People Who Want to Track Their Fitness