For 15 years, Blazie Engineering's Braille 'n Speak—with a braille keyboard and speech output, joined later by its Braille Lite— identical with the addition of a braille display—dominated the adapted notetaker market. Both included simple word processing, a calendar, a clock, and a calculator. In June 2000, Pulse Data took the accessible personal digital assistant (PDA) to another level by introducing the BrailleNote, built on the Windows CE operating system—the "brains" behind Pocket PCs, such as the Hewlett-Packard Jornada series. Now users have another choice—a product with all the features of the Braille Lite, plus the ability to send and receive Windows-based e-mail and to import, read, and save Microsoft Word files.

In this article, we evaluate the BrailleNote and the Braille Lite Millennium, Freedom Scientific's answer to the BrailleNote. (Freedom Scientific was formed as a result of a merger of three companies, including Blazie Engineering. Each company also has a product with a QWERTY keyboard and a braille display as well as one with either a QWERTY or braille keyboard and no braille display. See Product Features and Product Ratings in this article for more information.

BrailleNote

The BrailleNote's case is gray, and the braille keys are green. On the top surface of the unit, which measures 9.5 inches x 5 inches x 1 inch (the 32-cell model weighs 2 pounds, 9 ounces) are nine keys (representing an eight-dot braille keyboard plus a space bar) arranged on a curve for comfort. At the front of the unit is an 18- or 32-cell refreshable braille display, and below it, on the narrow edge facing the user, are four "thumb keys" used for moving forward and back through documents and menus. The 18-cell and the 32-cell units each come in the same size case, and it is possible to upgrade from 18 cells to 32 cells. Above each braille cell is a touch cursor, which, when pressed, routes the cursor instantly for ease in editing. Other physical features of the unit include a PCMCIA slot (through which the optional disk drive accessory and other devices can be attached), serial port, parallel port, modem connection, AC adapter, earphone jack, and infrared port. The BrailleNote also includes a rechargeable nickel metal hydride battery.

Users of the KeyNote or other HumanWare products will recognize the KeySoft suite of applications with its proprietary KeyWord word processor, KeyPlan appointment calendar, and so on. Although the fact that these applications are proprietary could be a drawback, KeyWord files can be converted and exported to be read as Microsoft Word documents on another computer, and Word documents can be imported and read as KeyWord files. One important distinction is that no conventional Windows programs can actually be loaded and run on the BrailleNote.

The feel of the BrailleNote's keyboard is solid, and the keys are quieter than they were originally. You can enter data quickly and accurately without losing characters or running words together. The presence of a Backspace key and an Enter key means faster typing and fewer multiple-key commands. Speech rate, pitch, and volume can be adjusted from the keyboard without using a menu.

The speech quality is very good. Speech and braille are independent of one another, so that one or the other or both can be active at any time. Some information, such as the announcement of the current file format other than KeySoft when saving files, is available only via speech.

The BrailleNote's commands within various functions are often issued by key combinations, or chords, involving holding down some of the braille keys along with the backspace or space bar; other functions are activated using combinations of the four thumb keys. Access to almost all menus is available from anywhere within the unit via the Task List (accessed by pressing the space bar with the letter O). For example, if you are in a word processing document and want to schedule an appointment, the calendar is just a few keystrokes away. One major exception is that the File Manager, used for copying, erasing, and renaming files, is not on the Task List. It is necessary to exit the current application, go to the File Manager via the Main menu, and then reopen the application.

Getting Started and Getting Help

The online manual is easy to use and can be accessed quickly from the Task List. In the online menu, you are then given the choice of Table of Contents or Index. After you choose an option, you can move through the topics listed by chapter or alphabetical listing, respectively. There are problems with some entries in the manual. So, when you choose "time set" in the index, you get the message "cannot find reference file." We also found many typos throughout the manual.

Although moving through action menus and sets of instructions in the BrailleNote is relatively straightforward, we did find the inconsistency of methods somewhat disconcerting. In some instances, the space bar advances through a menu. In others, the Enter key is required. In some places, the dots 3-4-chord (dots 3-4 with the spacebar) was required for going forward. On the other hand, help (the letter h plus the space bar) is available throughout BrailleNote's functions, and was useful and reliable.

You've Got Mail

The BrailleNote can send and receive e-mail, including messages from Windows-style accounts accessed using Microsoft's Outlook or Qualcomm's Eudora. The unit is equipped with an internal "soft" modem, as well as the option of connecting a PCMCIA modem or external modem to the serial port. You can open and read attachments in text and Word formats.

The e-mail function could be a lot smoother. It is possible to leave your mail on the server. But it is not possible to log on and send messages you have written without the BrailleNote first checking for and downloading new messages. With KeyMail, you dial up your Internet service provider (ISP), receive all messages, send all messages, and disconnect. While offline, you can reply, forward, delete, or save messages.

The BrailleNote performed much more reliably when sending and receiving e-mail from a single-line phone, such as those generally found in personal residences, but had considerably more difficulty on multiline systems that are common in work environments. It also performed more reliably if the number of messages to be received was not greater than 20 at any given time. If you are using the BrailleNote to check mail only occasionally, you may prefer to leave messages so you can read them again when you log on with your primary computer. On the other hand, if you are using the BrailleNote to access e-mail repeatedly—while on a business trip, for example—you will want to have messages deleted after you read them.

The BrailleNote gets "stuck" often, receiving only some of the messages on the server, and getting locked somewhere midstream. Since it frequently gets stuck with extremely large messages, it is wise to keep those messages on the server for a later time. You can tell KeyMail to ignore any messages larger than, say, 40,000 characters. When KeyMail encounters a message that is too large, it offers you the options of obtaining header message information, choosing to skip the message entirely, asking to see the first 10 lines of the message, or proceeding with downloading it. Again, this feature works only some of the time.

In earlier versions of KeyMail, some messages received were rendered unreadable by HTML code. Now, when messages are received in HTML, KeyMail strips away the excess verbiage regarding color and font and other annoying details.

Taking Notes

Some of the BrailleNote's speech-review and edit commands will be familiar to users of other notetakers. However, the BrailleNote's default editing mode is insert mode. So when you find a typo, you can simply type the correct character, and it will be inserted on the spot. When you give the command to delete a sentence, paragraph, or other large block of text, the BrailleNote asks for confirmation. This useful feature prevented us from deleting important information a few times.

The Key Announce feature lets you review BrailleNote commands quickly. The context-sensitive help is effective in the word processor and elsewhere. The spell checker works well.

The BrailleNote can import and read Word 2000 and WordPerfect 5.1 files. Files can be converted and exported in other formats through the file manager.

When you manipulate a file in any way—save, copy, delete, and so forth—BrailleNote asks you for the source and/or destination drive. The choices offered are Flash Disk, KeySoft System Disk, and Storage Card. Since everything in the BrailleNote has a "key" theme (KeyWord, KeyMail, KeyPlanner), we assumed that KeySoft was a handy storage space for quick storage. As it turns out, KeySoft was never intended for this purpose but, rather, as the drive for BrailleNote system files. Thus, when a hard reset was necessary, a devastating loss of data occurred. Nowhere in the product documentation was it indicated that data should not be saved in this manner.

Block commands are easy to use and effective. It was easy to copy a name and address from a file in the word processor and paste it into the address book. A handy feature is the Read Block command, which does just that. However, there is no indication on the braille display of where the text you have selected in a file begins or ends.

Did I Write That?

The braille translator is a problem. It violates some rules of braille translation, such as inserting a space between whole-word contractions like for and the. It also inserts a space between the words to and by and the following word. So, when you back-translate a file from braille to text or Word format, many instances of the word by become the word was, and the word to turns into an unattached exclamation point. The back-translator also has trouble with hyphenated words—the ar contraction in 35 year old, for example, does not back-translate.

Planning Your Life

The KeyPlan planner lets you schedule, reschedule, and set alarms to remind you of appointments. You are simply asked to enter the day, time, and name of an appointment and then to indicate whether you want to set an alarm to remind you of that appointment. Appointments are stored and can be reviewed, in chronological order by appointment, no matter what order you schedule them in. One of the first things you will want to do is to choose Setup Options from the Planner menu and lower the alarm volume from its disturbingly loud default setting.

Little Black Book

The KeyList address list lets you maintain your phone book of contacts. Data entry is straightforward. Each entry contains a wide variety of fields, including work and home e-mail and fax numbers. The address list is used for the KeyMail function.

Remote Possibilities

The BrailleNote can function as a speech synthesizer or braille display with a Windows-based screen reader that has the appropriate driver. We used it with Window-Eyes and it worked well in both capacities. It is still possible to look up a phone number or schedule an appointment while the BrailleNote is functioning in either of these modes.

Braille Lite Millennium

In addition to the popular features offered in previous versions, the Braille Lite Millennium M20 (20 braille cells) and M40 (40 braille cells) offer an improved speech synthesizer, the ability to send and receive e-mail with a built-in modem, and several other interesting new features.

One of the first notable changes in the Braille Lite Millennium is the appearance of the unit itself. Visually, the case is a dark blue with silver flecks. Tactilely, the unit has several additional ports, two small wheels near the Braille display, and what seems like two on-off switches.

The Braille Lite Millennium uses a new speech synthesizer that should sound familiar to anyone who has ever used the Double Talk synthesizer. The unit's speech emanates from two built-in speakers that are larger than in the previous versions. The increase in the size and number of speakers improves the listening experience, though the voice leaves something to be desired.

The second on-off switch, located on the left edge of the unit, is the braille display mode switch. This new feature allows persons who use their Braille Lite as a refreshable braille display to change from braille display mode to notetaker mode at the flick of a switch. When you are reading text from your computer and need to jot down a phone number or appointment, you simply flip the switch to notetaker mode. When finished, you flip the switch back to display mode and continue reading where you left off. When the switch is turned, the Millennium announces in both speech and braille the status of the braille display mode, preventing accidental switches of modes.

The Braille Lite M40 has four ps2 type ports, and the M20 has two such ports. One of these ports is a standard serial connection, and one is used to connect the unit to a disk drive. The remaining two ports on the M40 are for future use only. As was the case on older versions, the Braille Lite Millennium has a standard parallel port and headphone jack.

One of the most interesting new features in the Braille Lite Millennium is the introduction of Whiz Wheels—small rubber wheels on either end of the refreshable braille display. Each of these wheels can be used to scroll the display up and down. Depressing each wheel allows you to select whether each turn of the wheel will scroll the display a line, sentence, or paragraph. These wheels can be set separately so that you could, for example, set the left wheel to scroll by line and the right wheel to scroll by paragraph. The size of these whiz wheels may be an issue. Users with large fingers or minor difficulty with motor skills may have a problem turning the wheel only one click.

Getting Help

One of the major problems we found with the Braille Lite Millennium is incorrect or missing product documentation. The user manual incorrectly describes the layout of the ports on the M40. While the documentation is correct for the users of the M20, the discrepancies between the documentation and the reality of looking at the unit will cause confusion for users of the 40-cell model. Also, nowhere in the supplied documentation is the process of inserting a CompactFlash card into the machine described. While this process can be figured out by most users with a bit of trial and error, since this is relatively new technology, an explanation of the process would be useful.

Braille Display

The Braille Lite Millennium's braille display is similar to the braille display in previous versions. Each cell has a cursor routing button, and the unit contains scroll bars. As of this writing, a continuous scroll mode had been implemented but still had some problems. You can initiate continuous scroll and control the speed of scrolling, but the only way to turn off continuous scroll is to turn off the unit.

Silence Is Golden

In the September 2001 firmware revision, Freedom Scientific brought the silent start feature to the Braille Lite Millennium. As in previous versions of its notetakers, the unit is supposed to start silently when the space bar is held down during power on. In reality, the Braille Lite Millennium does not speak when the silent start option is invoked, but it does produce a loud beep.

CompactFlash

CompactFlash is a technology camera that manufacturers use to store pictures from a digital camera on small cards (about half the size of a credit card) called CompactFlash cards. These cards are relatively inexpensive and can be purchased in sizes from 16 to 128 megabytes from most camera and office supply stores. The Braille Lite Millennium can store data on these cards, which fit into a slot on the back of the unit. A built-in utility allows you to move files between the Braille Lite Millennium and the CompactFlash cards. These cards are only for storage; files cannot be edited or read while on a CompactFlash card. This feature is great for quickly backing up the contents of the notetaker. The external program used to move files between the card and the notetaker is a bit tricky at first, but once you understand how it works, it is fairly straightforward.

You've Got Mail

With the release of the Braille Lite Millennium, Freedom Scientific has finally caught up to its competition in the sense that it allows its users to send and receive e-mail with their note takers. E-mail is accomplished with a built-in modem and several external programs. The disadvantage to this approach is that if your notetaker loses your data or if these programs become corrupted, you have to reload them before you can access your e-mail. Before you can send and receive mail, you have to run a program called Wizard that prompts you for your user name, e-mail server, and the phone number of your ISP. When prompted for sensitive information, such as account password, the Braille Lite Millennium echos keystrokes, rather than hides this information. It then repeats your password and asks you to confirm it by typing y or n. Once the Wizard completes the setup process, it stores all your information in a file called "email.cfg." Again, all your information is contained in this file, which could be a huge security risk. One advantage of this method of storage, however, is that "email.cfg" is a readable file, making it fairly simple to reconfigure your e- mail information manually.

Sending and receiving e-mail with the Braille Lite Millennium is fairly simple. The program contains all the standard e-mail functions, including an address book. It also allows you to send messages with attachments. The unit is compatible with Windows- based e-mail. However, the only attachments it can receive and read are text files. During our review, the mail software occasionally locked up the unit, and we were forced to turn the unit off and then on to restore normal operation. When contacted, the technical support person stated that this problem was partially caused by the mail program having been converted to a multilingual application. We were sent an additional file to load that solved the problem.

Taking Notes

The Braille Lite Millennium's feature-rich editor allows for easy insertion, deletion, and navigation of text. Cutting and pasting text is accomplished using the clipboard. In previous versions, the clipboard was used for cutting, pasting, and inserting text. It worked fine until you needed to insert something between the time you cut text and the time you pasted it. In the Braille Lite Millennium, these two operations have been separated, allowing you to insert text at any time without fear of overwriting anything.

PC Editing is a feature for people who want their notetaker to behave more like their standard word processor. It allows you to decide if text entered while reading a document will be appended to the end of the file, inserted at the current cursor location, or will overwrite text at the cursor location. In previous versions, a change in voice indicated which of these three modes you were in. This change-of-voice feature is not in the Braille Lite Millennium.

The Braille Lite Millennium's powerful search features let you search within the current file or across multiple files for a specific string of text. You can even do a search and replace by combining macros with the search capabilities. A macro can, for example, open a frequently used file with a single keystroke or display the time automatically when the unit is turned on.

Little Black Book

The Braille Lite Millennium's date book feature is fairly simple to use. During testing, we were able to check appointments only by day—the check appointment-by-hour feature did not work properly.

Manufacturers' Comments

Pulse Data

"Much time, energy, and resources are being channeled by Pulse Data International (PDI) and HumanWare technical staff to further enhance the functionality and innovation that the BrailleNote family of Personal Data Assistants offers to consumers who are blind. KeySoft version 3.06 will unify the respective versions of software used by the six models of BrailleNotes/VoiceNotes. HTML filtering in e-mail messages, improved efficiency for sending and receiving e-mail, enhanced Microsoft Word convertibility, fixes to the BrailleNote's braille translator, and foreign language support for German, Italian, French, and Spanish will all be features either improved upon or implemented into the KeySoft 3.06 field upgrade; the members of the PDI group recognize the importance of updating its documentation for these products to reflect these changes. The Pulse Data Group expects to release and ship its first version of BrailleNote GPS, a navigational tool that further enables persons who are blind to navigate effortlessly throughout a given environment while taking advantage of the latest advances in "mainstream" technology. Plans for a "software developer's kit" are under way and should be available by the first quarter of 2002 for third-party programmers who want to create Windows CE applications that can be run on the BrailleNote."

Product Information

Product: BrailleNote, 18- and 32-cell

Manufacturer: Pulse Data International Limited; phone: 64 3 384 4555; e-mail: sales@pulsedata.com; web site: www.pulsedata.co.nz. U.S. distributor: HumanWare 6245 King Road Loomis, CA 95650; phone: 800-722-3393 or 916-652-7253 e-mail: info@humanware.com; web site: www.humanware.com. Price: BrailleNote 18 $3,799 plus $45 shipping; BrailleNote 32 $5,499 plus $45 shipping, Service available from AT&T Wireless, T-Mobile, and others. Check with your local service provider.

Freedom Scientific

"Freedom Scientific appreciates the review of our Braille Lite M20 and M40 notetakers and the opportunity to clarify a few points made in the article. CompactFlash cards are covered in a separate document (cf.txt), which is on all shipping units and our web site as a free download, as is the addendum for the Braille Lite M20 and M40.

There are three firmware updates scheduled for both units between now and July 2002 where we will continue to enhance the double talk.

If users want a completely silent start, they can turn the speech off to avoid the confirmation tone feature with silent startup.

Because the Wizard used to set up e-mail can be run anywhere any time, users have told us that the confirmation of password is more important then confidentiality.

Product Information

Product: Braille Lite Millennium M20 and M40

Manufacturer: Freedom Scientific Blindness and Low Vision Group 11800 31st Court North St. Petersburg, FL 33716 phone: 800-444-4443 or 727- 803-8000 fax: 727-803-8001 e-mail: Sales@freedomscientific.com; web site: www.freedomscientific.com. Price: Price Braille Lite Millennium 20: $3,495; M40: $5,595.

****

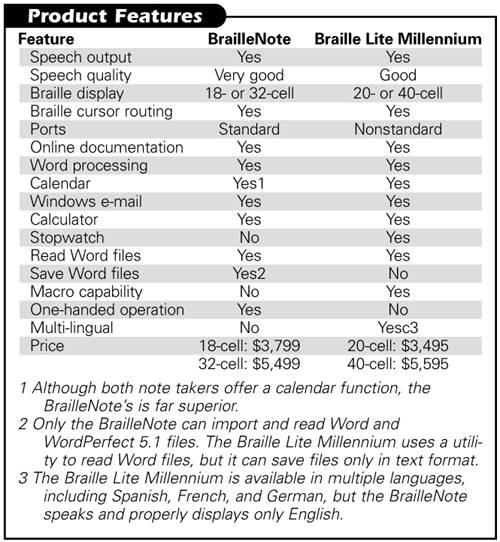

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

****

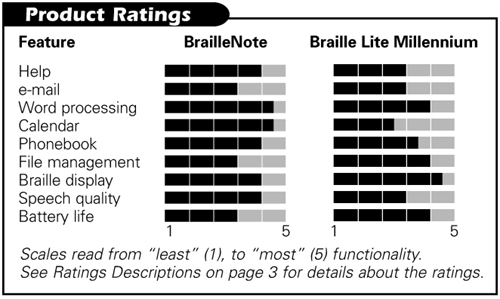

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text