Focus on AFB: Summer 2022

- 2022 AFBLC Created Connections Across a Diverse Array of Participants

- AFB Talent Lab Launches With First Group of Interns and Apprentices

- Research Roundup: Journey Forward Shows the Need for Continued Access Improvements

- Bojana Coklyat: What Does the World Look Like to You?

- News

2022 AFBLC Created Connections Across a Diverse Array of Participants

Attendees left feeling enthusiastic about the future of inclusion at work and more.

True to its theme of “putting inclusion to work,” the 2022 AFB Leadership Conference (AFBLC) brought together a diverse array of leaders in the blindness field, major corporations, and accessibility experts. Nearly 300 people attended the AFBLC to learn, share ideas, and network, with an emphasis on how they’re working toward greater inclusion. What’s more, there were many opportunities for attendees to talk about ways to make even more progress toward achieving that goal.

“The attendees were fully engaged,” says Sylvia Stinson-Perez, chief programs officer. “I heard people saying when they left that they were re-energized—and I felt that way, too. Everyone left feeling inspired to take action.”

Some of that had to do with the nearly 50 presenters, including speakers and panelists, which she describes as “excellent.” They included United States Access Board Executive Director Sachin Pavithran, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) consultant Catarina Rivera, and Tony Coelho, the primary author and sponsor of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) as keynote presenters.

Stinson-Perez says attendees valued the chance to connect in person again, as well as the quality of the networking opportunities.

A particular favorite among participants was the “ideathon" facilitated by the JPMorgan Tech for Social Good Team. Attendees from different disciplines—such as education, nonprofits, and corporations—were brought together at tables to brainstorm about inclusion and accessibility, not just in digital products but also in everyday activities and products. According to Stinson-Perez, almost every table brought up the difference between “accessibility” and “usability.”

“Something might be accessible, but is it easy to use and delightful? Because if it’s not, people won’t use it,” she explains. Stinson-Perez says the ideas generated were gathered and will prompt follow-up conversations.

Another highlight of the AFBLC was the participation of 27 fellows and mentors from the Centennial cohort of AFB’s Blind Leaders Development Program (BLDP). They helped organize events, one of which was a “Dine-around” event on the first night, an idea borrowed from VisionServe Alliance, says Neva Fairchild, who oversees the BLDP.

“When people come to conferences, sometimes you find someone to have dinner with and sometimes you don’t,” she explains. “People who signed up were assigned to tables of eight at a local restaurant, and members of the BLDP chose the restaurants, made the reservations, and got links to all the menus. That went off very successfully.”

Fellows and mentors also introduced breakout sessions and stood at the door of each room to welcome attendees. According to Fairchild, both people who were blind and sighted appreciated the hospitality and knowing they were in the right place.

“We wanted to give members of the cohort a chance to get in front of a crowd with a microphone and present themselves,” she says. “They also participated in all the sessions—and fellows had professional headshots taken.”

Fairchild adds that mentors were equally involved in the BLDP activities, because “leaders are learners,” she says. “Several of the fellows said the conference was ‘transformative.’ They were completely blown away by all the opportunities to meet people, network, make connections, and have their horizons expanded. And I heard many of them say, ‘I’m not stopping here. I’m going to keep stretching and growing.’ So they experienced an increase in their confidence.”

Of course, the AFBLC would not be complete without celebrating the accomplishments of groundbreaking leaders in the blindness field.

The 2022 Migel Medal was awarded to Gale Watson and Judith Dixon. Watson has worked in clinical care, education, and research at many levels throughout her distinguished career, and most recently was the director of Blind Rehabilitation Service for the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dixon is a recognized trailblazer in the areas of braille reading, writing, and promotion, as well as technology and e-literacy. She has served as an advocate for access to printed information through the widest possible use of special formats.

Rachel Longan was the 2022 recipient of the newly established Llura Gund Leadership Award, which recognizes an outstanding leader who has benefitted from one of AFB’s employment initiatives. Plus, it provides $5,000 to support their leadership development beyond AFB’s training programs. Longan is a Licensed Marriage Family Therapist who also founded the Mind’s Eye, a support group for individuals coping with blindness. She previously founded a support group for LGBTQ individuals with vision loss.

The 2022 Corinne Kirchner Research Award was presented to Rona Pogrund, Ph.D., a teacher of students with visual impairments (TSVI) and Certified Orientation and Mobility Specialist (COMS); Shannon Darst, Ph.D., TSVI, COMS; and Michael Munro, Ph.D., TSVI. Their work culminated in the Visual Impairment Scale of Service Intensity of Texas (VISSIT), which is changing the way itinerant vision professionals determine the appropriate type and amount of service each student with a visual impairment should receive to reach their full potential.

Learn more about the honorees and their outstanding work in AFB’s awards announcement.

AFB would like to thank all of the participants, attendees, speakers—and particularly the sponsors who helped make the 2022 AFBLC a success.

“People were really connecting and finding ways to collaborate, which I think is a very powerful,” Stinson-Perez says.

AFB Talent Lab Launches With First Group of Interns and Apprentices

The program educates computer science talent and assistive technology users in building more inclusive technology.

There’s an increasing demand for fully accessible digital tools, like websites and apps. But finding people with expertise in accessibility isn’t quite so easy, because it’s rarely taught in computer science education – and if it is, it’s usually high-level and often expensive.

For more than 20 years, AFB has helped companies improve the accessibility of their technology through AFB Consulting, which always believed in building in accessibility from the start rather than patching existing systems. AFB Consulting’s skilled team of tech designers, engineers, and project managers worked with countless companies over the years, but AFB wanted to scale our impact.

“Our work was very localized to the individual jobs we were doing, but in terms of the overall issue of the gap in digital inclusion, we really weren’t moving the needle as far as we wanted to,” says Kristin Reuschel, Program & Curriculum Manager. “Accessibility is not a standard from accrediting bodies, so instructors have no reason to know it. We’re obviously good at training people, because they kept getting hired by other companies and promoting the skills they learned here. So we decided to become the teachers ourselves.”

That’s why AFB Consulting is now AFB Talent Lab—an educational program for college students and career seekers interested in digital accessibility.

“Our folks were very attractive to other employers because they have a rarified skill set, and we really wanted to turn that into an asset,” Reuschel says. “And it’s important for people with disabilities to be advocates and team members in that space. Sometimes people in the digital space have good intentions, but they don’t have the lived experience. Diversity, equity, and inclusion is very trendy, but it often doesn’t include disability.”

AFB Talent Lab’s first cohort began on June 6 and includes five apprentices and 11 interns, who are being led by five mentors. All of the interns and apprentices are paid – because computer science is a competitive field – and receive extensive training and hands-on experience. The AFB Talent Lab instructors and mentors have vast expertise in digital inclusion, developed through accessibility consulting projects with leading businesses such as Google, Samsung, and Microsoft. What’s more, many of them launched their own careers through AFB internships.

The college-age interns begin by working full-time over the summer, and have the option of continuing part-time in the program’s fall and spring semesters. The program includes remotely delivered foundational coursework in digital inclusion, which was built from scratch by AFB Talent Lab, since it’s the only program of its kind, as far as AFB knows, Reuschel says. Interns also have opportunities for job shadowing and direct experience with clients, working in product testing, accessibility, and more. Apprentices, who are all assistive technology users, have much the same learning and work opportunities as interns, but must commit to two years and their program includes a robust project management curriculum and will result in certification and a journeyman's card. At the end of the program, both high-level interns who complete multiple semesters and apprentices will receive digital badges and can request letters of recommendation.

“We compare it to a teaching hospital,” Reuschel says. “Much like an intern might insert an IV, interns and apprentices will be supervised by an expert mentor, so the companies we work with can be confident they’ll receive a high-quality product and want to continue working with us.”

AFB Talent Lab will continue building on the initial program, as well as seeking more partners to provide project work or sponsorship for the program.

“Scaling our impact was our original motivation, to close the accessibility skills gap,” Reuschel says. “Although we’re an educational program, not an employment program, we want our participants to be employed—and create accessible, inclusive work environments.”

For more information on AFB Talent Lab, including partnership opportunities, visit the program website.

Journey Forward Shows the Need for Continued Access Improvements

New research report finds people with vision loss still face challenges in the COVID era.

As a follow-up to AFB’s Flatten Inaccessibility report, which studied the impact of COVID on people who are blind, low vision, or deafblind, our research team conducted the Journey Forward survey. In July and August 2021, the team dug deeper into topics identified in the initial study, including digital accessibility barriers, transportation and safety challenges, and access to healthcare, food, and medical supplies.

The recently released Journey Forward research report reveals that survey participants continue facing many of the same challenges they did during the Flatten Inaccessibility study, conducted in April 2020. Plus, with the introduction of vaccines and more availability of COVID testing, new issues have come to the surface.

“Journey Forward is a great sequel to Flatten Inaccessibility, because a good chunk of time passed between the two studies,” says Carlie Rhoades, Ph.D., program metrics and evaluation specialist.

According to Arielle Silverman, Ph.D., AFB’s new director of research, most of the findings confirmed that Americans who are blind or have low vision have had their lives affected in ways that demonstrate a clear inequity from their sighted counterparts.

“There are still the same accessibility barriers,” she explains. “Just because some restrictions are being lifted, people still have challenges in areas such as transportation. And the lack of access to telehealth is going to be an ongoing concern – that need isn’t necessarily going to go away.”

Rhoades says what struck her most was the significant lack of access for people who don’t drive, making it very difficult to go to a medical appointment, get a COVID test or a vaccine, or pick up groceries or prescriptions.

“There was such an emphasis on drive-through services and having things delivered,” she explains. “If you have vision loss and are unable to drive, that’s a major, critical problem. People really had trouble getting access to transportation, especially with safety concerns related to public transportation, paratransit, and ride-sharing services.”

In fact, transportation access was a cross-cutting factor in every area where people who are low vision face challenges during the pandemic, along with the lack of digital inclusion. For example, the survey data showed that many websites and apps used to schedule appointments, order groceries, or even find data about local COVID rates were inaccessible with many types of screen readers and screen enlargement software. That means even having essential items delivered was an issue, especially for some older adults who reported having limited experience with technology. Many people were forced to rely on others to schedule vaccine appointments and help them navigate other issues, but not everyone has someone to assist them with these tasks.

Additional key findings in the report include issues with inaccessible prescription labels, and concerns about being able to monitor safety such as physical distancing and mask-wearing by others.

“Some of the statistics and recommendations from the report will be used in policy advocacy, such as improving regulations for web and app accessibility,” Silverman says. “As a blind person myself, I couldn’t easily access a lot of the information sighted people could. These issues were only intensified because of the pandemic.”

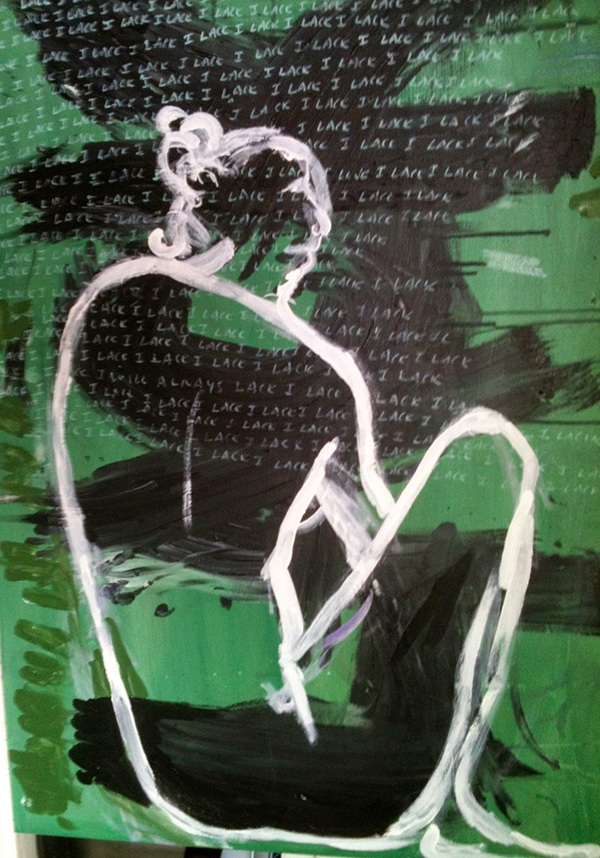

Bojana Coklyat: What Does the World Look Like to You?

We continue our series asking people who are blind or visually impaired to share their employment journeys.

Bojana Coklyat is an artist, disability activist, and former project manager for the NYC Museum, Arts and Access Consortium, where she helped ensure that museums and art spaces—including virtual ones—are accessible and welcoming to all people with disabilities. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Art Therapy and a master’s degree in Disability Studies and Art Administration. She received a Fulbright grant and spent a year researching access in the Czech Republic and their arts and cultural institutions. She’s also a consultant and co-producer on Worlds We Live In, a documentary film commissioned by AFB that demonstrates Helen Keller’s legacy of advocacy and achievement through the voices of a diverse array of today’s blind community. As a visually impaired person on the film production team, she brings her unique perspective and connections to the creative process.

When did you first experience vision loss?

I’ve had type 1 diabetes since I was 10 years old. In 2007, I was working in retail and suddenly couldn’t read a price on something. I thought I just needed glasses, but I was eventually diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy and macular degeneration. My vision continued to deteriorate for a while, but I still have some vision and it’s been fairly stable over the past 10 years thanks to a kidney and pancreas transplant that helps stabilize the diabetes.

What surprises people about your life?

Have you ever been in a situation where people tried to put limits on your aspirations because of your visual impairment? How did you have to advocate for yourself?

When I was studying for my master’s, there were two computers that hadn’t been updated in 10 years and the screen reader software wasn’t working. When I brought it up they just said they didn’t have the money to upgrade and I was the only one who had asked about it—which I know was baloney because there was more than one blind person at the school. Or professors at all the schools I attended who just wanted me to gloss over certain things they thought were too hard for me. I said, “No, I want to do this. Let’s figure out a way to adapt it together.” I wasn’t just talking about accommodation. It’s about honoring our civil rights.

What do you wish more people understood about what it means to be blind or visually impaired?

When I’m in my apartment, I’m not stumbling around trying to figure things out. I know how to cook, how to make my bed—how to arrange for a ride-sharing service or get to the grocery store with my cane. My vision loss is only a challenge when, for example, I need to read something at a store and no one is available to help me, or I want to experience a movie but the person working there can’t find the audio description device. I also have people who think I’m faking being blind because I still have some vision. They don’t understand the spectrum of vision loss.

What would true inclusion look like to you?

True inclusion would mean we eliminate ableism. Which is like saying, “Let’s eliminate racism” or “Let’s eliminate sexism.” Obviously there are people who are allies, but the sighted world is mostly an ableist world that doesn’t see blind people as equal. Maybe they devalue blindness, or don’t want to take the time to understand. They just want to carve out a little part of their world for us. So we need a total overhaul of this thinking that’s rooted in just one way of viewing people and one way of valuing people for so long, and that goes for any marginalized group.

News

AFB’s commitment to improving digital inclusion was front and center at the 2022 AFB Leadership Conference. There were two panels devoted to the topic, which demonstrated how we’re engaging with other organizations in advocacy, the exploration of new communication technology and tools, including those on the near horizon, and making sure laws adapt to ever-changing technology.

“We had a great opportunity to get the message out to attendees that there has to be a more systemic approach to digital accessibility,” says Sarah Malaier, senior advisor, Public Policy & Research, who participated in the first panel and moderated the second.

The first panel discussed how AFB and some of our partners—American Council of the Blind (ACB), National Federation of the Blind, and National Disability Rights Network—are working to advance digital accessibility. Topics included opportunities and challenges, and practical and legal challenges the Department of Justice (DOJ) will be considering based on the letter AFB and our partner organizations sent to the DOJ with the support of 181 organizations across the disability and civil rights community. The letter asked that the administration commit to finalizing a rule on web and application accessibility before the end of the current administration. Within three weeks of receiving the letter, the Department of Justice issued guidance on the obligations that state and local governments and businesses open to the public have to make sure that their websites are accessible to people with disabilities.

During the second panel, which included experts from Communication Service for the Deaf, ACB, and National Association of the Deaf, the discussion centered around the past, present, and future of the 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act. In effect for about 12 years, the legislation has been successful in improving and expanding access to audio description and giving the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) the authority to pursue other accessibility requirements related to communications and television.

“But the law has its limits,” Malaier says. “The FCC needs additional authority to help us move further into the future to address changing video consumption habits as people tend to move toward the internet. Also, we’re learning that audio description is very doable and there are opportunities to expand it to a larger number of stations and geographic areas.”

AFB will continue working with other organizations to make sure accessibility laws adapt to the world’s rapidly evolving technology.