Helen Tours the Middle East: Egypt

February 9, 2012

2012 marks 60 years since Helen Keller toured the Middle East; namely, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel. Helen was entranced by the Middle East and wrote about it to her friend and colleague Georges Raverat, the Director of the American Foundation for Overseas Blind (now Helen Keller International) in Paris. During her visit, Helen met leading cultural and political figures of the region, including the Egyptian writer and intellectual Taha Hussein, Queen Noor of Jordan and Golda Meir, Israel's Foreign Minister. Her letter to Raverat makes fascinating reading, so I thought I would share it, country by country, over multiple blog posts. I'd love to get your feedback, and if you happen to know how perceptions of blindness and advocacy in any of these countries have changed (or haven't!), please let me know in the comments!

Here's how she begins her letter to Raverat in 1952:

...my trip through the Near East. It was more wonderful than I had dreamed for us to travel through semi-legendary lands where, like the stones [sic — stories?] in the "Arabian Nights" the peoples had slept during the night of the ages and been awakened by the voice of a new day. I could still feel something of the old picturesqueness, the poetry, the oriental atmosphere and the spirit of prophecy, and I was fascinated by the power of the Moslem religion.

And here is an excerpt from the portion of the letter in which she talks about Egypt:

Egypt is in the very heart of Islam. Having read about the anti-British riots, I could not help wondering how it would fare with us in our work in Egypt. To my surprise the people we met showed us warm friendliness, and were most hospitable. In Cairo I addressed the Medical School, students from the different colleges at a big meeting in Dhakema and the American University on prevention of blindness and the urgent need for rehabilitation for the blind throughout Egypt. We visited the few schools that exist for children without sight. I was grieved to find what meagre openings the adult blind of Egypt have for reeducation or employment. The good school at Zeitoun and the workshop for the blind established by the Government and the splendid school for deaf girls owe their existence to the untiring perseverance and unbreakable optimism of Mr. Sayed Fattah, a jolly, lovable personality whose jokes made me laugh away difficulties whenever we met. As on of the charming, progressive Egyptian women said to whom I was introduced, "our people have a strong will-power, but you must make them believe in a movement before they support it." How true that is of the work for the blind and the deaf!

For years I had read about Taha Hussein Pasha, and I cannot express my delight one day when he visited me at the Semiramis Hotel, bringing his wife and son, and stayed a whole hour. I was privileged to touch his face, and how handsome, scholarly and full of inward light it was! His responsive tenderness warmed my heart, and I felt as if I had known him always. We discussed many topics — Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Plato and Socrates, the liberating power of philosophy, Taha Hussein's studies of the great blind Arab philosopher of the tenth century and his work for the blind. He told me that while he was Minister of Education, he had worked quietly enabling capable blind persons to go to universities and colleges, and that he was still deeply interest in that measure. He said that one of the chief needs of blind students in Egypt was secondary schools from which they could go to finish their education in college. It was a precious boon to me to feel Taha Hussein's personality behind me when I called on various ministers of the Government and begged them to authorize those secondary schools. Finally the Minister of Education promised me that those schools would be opened, and Mr. Fattah was confident in his assurance that it would be done.

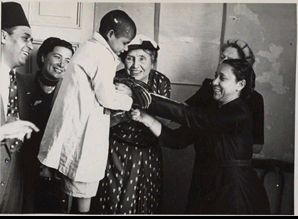

Polly and I took tea with the Noor society for the Blind in a delightful garden where there was a swimming-pool. To my surprise the President, Mr. Shalen, a handsome, distinguished man, paid me an exquisitely poetic tribute in which he said Louis Braille and I were the two eyes of the blind of the world, and I received from him and the Society a captivating little statue of the wife of King Akhnaton, the noblest soul that ever sat on the Egyptian throne!..."

Helen was an enormous success and her timing could not have been better, coming in April, just two months before Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew King Farouk. Kim Nielsen, in her book "The Radical Lives of Helen Keller," notes that the US State Department, unlike the CIA was unaware of the monarch's imminent overthrow. Helen's presence was an affirmation of US values at a time when America was becoming increasingly concerned about Egyptian sympathies for the Soviet Union.